Witchcraft – Bonus Episode

This week’s episode is a bonus episode on the history of witchcraft in English law. We give murder a rest in this episode and focus exclusively on the rise and fall of witchcraft in England in the 17th century instead. The episode starts by looking at King James I’s weird personal relationship with witch-hunting. We then see how his son, Charles I, was a bit skeptical about the whole thing, and how he fostered skepticism towards witch-hunting until his career was cut short (so to speak) and civil war broke out.

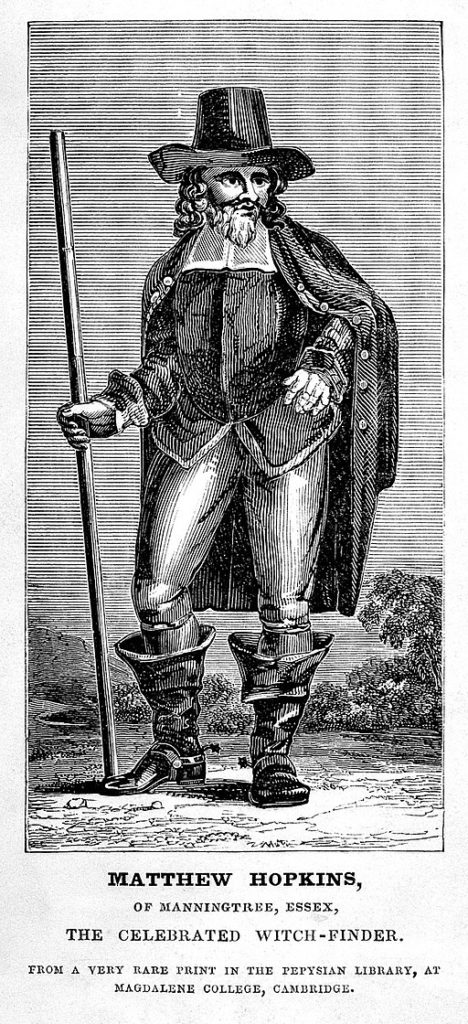

We then turn to the story of the so-called Witchfinder general, Matthew Hopkins, and his colleague, John Stearne, who were responsible for the executions of over one-hundred alleged witches during the English Civil War.

L0000812 Matthew Hopkins, Witch-finder..Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images.images@wellcome.ac.uk.http://wellcomeimages.org.

Finally, we’ll see that after the war, judges began to reject the idea that witchcraft could be proved in court, and how witchcraft prosecutions died out before witchcraft beliefs did.

Don’t worry if you are missing the history of homicide – we’ll be back with an episode on infanticide next time.