Episode 4: Unintentional Killing

Welcome to today’s episode on unintentional killing!

We all know (now) that if you kill someone intentionally, it’s murder. But is it ever murder when someone kills someone else unintentionally?

Today, we look at a whole range of unintentional killings and ask whether they’re murder, manslaughter, or sheer accident. Is it murder if you mean to kill one person but end up unintentionally killing another? What is it when you mean to give someone a little push or slap and end up killing them by accident? What if you mean to hurt someone really badly but end up killing them instead? And what if you just do something really stupid and kill someone by mistake?

Murder weapons vary widely in this episode. We’ll see a man who tried to poison his wife with an apple, a blacksmith who killed his apprentice with a bar of iron, a roofer who killed a pedestrian with a shingle, and a provoked man who killed a woman with an unlucky broomstick throw.

Warning: modern terms for what we’re discussing today vary widely, particularly in the USA. Depending on the jurisdiction, you can find not only different degrees of murder, but also degrees of manslaughter, as well as terms like felony murder and depraved heart murder.

Be sure to subscribe on your podcast app. Click here to subscribe to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. Follow us on Twitter @murderhistorian.

Sources and notes:

- Today’s story about the boys on the overpass is inspired by a real-life modern case. You can read a news article about it here and here. In this case, the boys brought things to the overpass to throw off it and they aimed at hitting the cars. The boy who threw the fatal rock pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and the others pleaded guilty to manslaughter.

- These boys shouldn’t be singled out though. Edward Coke and Matthew Hale, writing in the seventeenth century, also talk about people throwing stones into crowds. And there’s there notorious English case, R v Hancock and Shankland (1985), where two grown men dropped a concrete block on a road and killed a driver. In their defence, they said they only meant to intimidate the person in the car, not to kill anyone.

- The blacksmith and the broomstick case are reported by Kelyng. The comment about the box on the ears and the blow with a little with a stick are from Holt, in Mawgridge’s case. The story about the servant who shoots into the cornfield is from Hale. Kelyng and Hale both talk about the case with the roofer throwing tiles off a roof. The poison apple case is from Plowden.

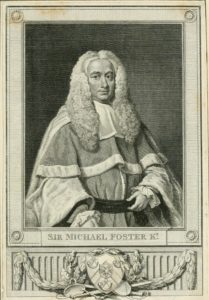

- While I refer to the idea of “great” or “grievous” bodily harm, the term doesn’t appear consistently in the law until the nineteenth century. Nonetheless, the idea of intending to do harm that’s likely to kill someone is distinguished from the idea of doing a little bit of harm much earlier than that. And Michael Foster writing in the mid-eighteenth century, emphasizes the distinction.

Michael Foster (1689–1763) – new century, new judicial hairdo. Foster is another one of my favourite sources on the history of murder.