Episode 3: Provocation

Today’s episode features a considerable amount of spontaneous stabbing. We start off with the famous case of Watts v Brains (1600), where the court has to deal with two major problems. First, is it OK to kill someone just because they make “a wry face” at you? Second, how do we prove malice aforethought (and therefore that someone committed murder) if one person kills another in the heat of the moment?

We go on to see how the famous judge, Sir Edward Coke, decides to solve these problems by changing the rules of the game. From now on, he tells us, we can just presume that it’s murder when one person kills another without provocation.

This brings us on a whirlwind tour of the idea of provocation. Can you be provoked by verbal insults? Rude gestures? Slaps? The loss of a stranger’s liberty? Adultery? What else? The answers may surprise you.

Notes on sources:

- Most of these cases are reported by Kelyng and Hale. I selected them (and they are the usual ones selected) because they are featured in Mawgridge’s case, decided by Holt in 1707.

- For the quote I read (and for a great article), see Kesselring, K.J. “No Greater Provocation? Adultery and the Mitigation of Murder in English Law.” Law and History Review 34, no. 1 (2016): 199-225. Accessed August 10, 2020.

- The Old Bailey stats come from Jennine Hurl-Eamon, ‘”I Will Forgive You if the World Will’: Wife Murder and Limits on Patriarchal Violence in London, 1690–1750,” in Violence, Politics and Gender in Early Modern England, ed. Joseph P. Ward (Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2008), 223–47.

- For more on provocation, see Horder, Jeremy. 1992. Provocation and Responsibility. Oxford Monographs on Criminal Law and Justice. Oxford: Clarendon.

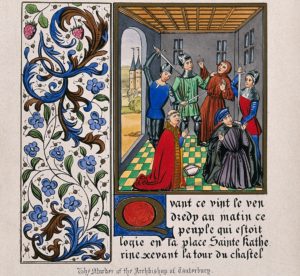

Who wore it better? From left to right, the Lord Chief Justices Sir Edward Coke (1613-1616), Sir John Kelyng (1665-1671) and Sir Matthew Hale (1671-1677).

I may have been a little unfair to Coke who was really just repeating the terms of the indictment in Mackalley’s case in the section I read aloud. But the case truly is a nightmare to read, particularly when compared with Kelyng and Hale’s writing, which is a lot clearer and more fun.